I have found the most extensive article written about Berry Hill Plantation! I was giddy when I started reading it. It was originally published in 1970 in the Record-Advertiser. It was written by Kenneth H. Cook. I decided to put together an article with all of my videos, the original article that Mr. Cook wrote, and my photographs along with pictures from the HABS site. Up above is my video tour of the interior that I made this past summer, with my special guest, Mr. Luck. He is the plantation historian. Such a lovely man!! I’ve created a gallery of pictures at the bottom of the post so be sure to swipe through those. I love the picture with the ladies in their hoop skirts out in front of the house!

Old House Life slave house ruin video. Click here.

Old House Life enslaved cemetery video. Click here.

The great article that Mr. Cook wrote in 1970 for the Record-Advertiser.

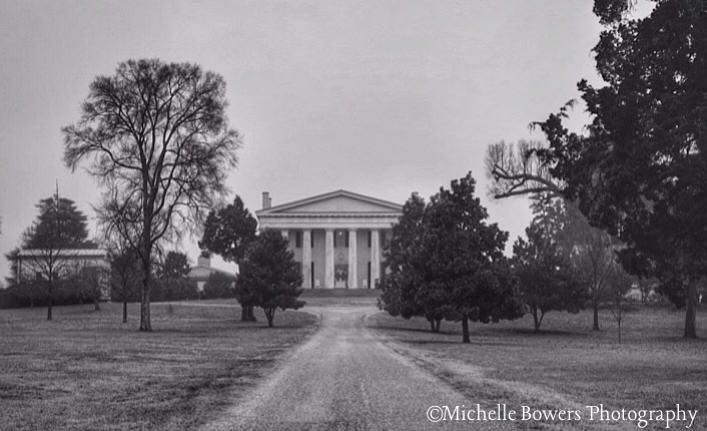

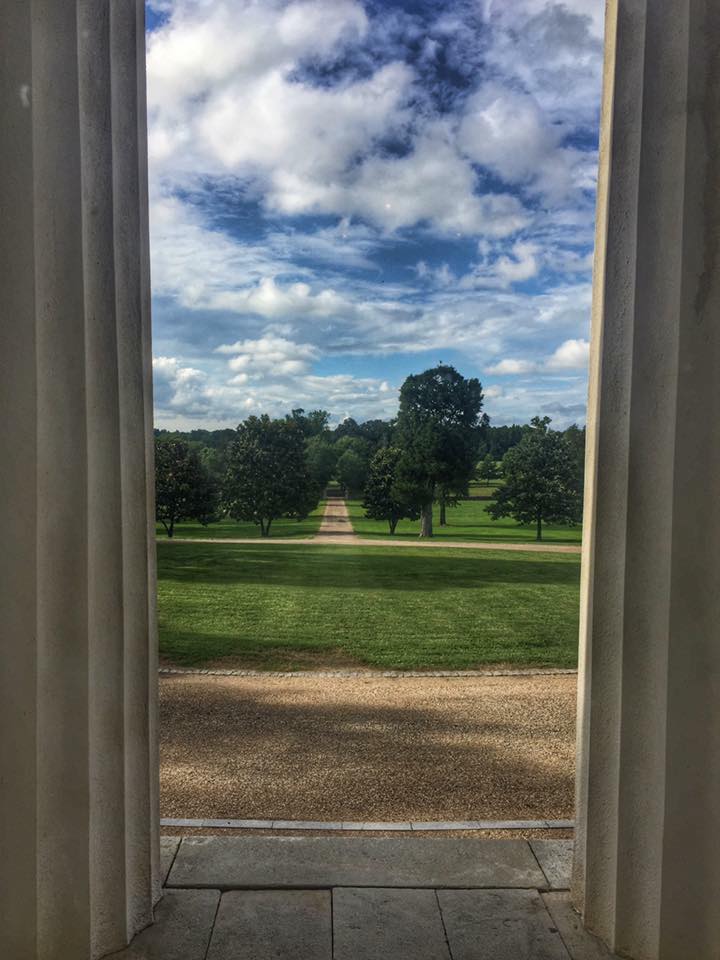

About three miles west of South Boston, on the north side of the Dan River, an inconspicuous farm road turns south off the River Road. The half-mile drive, once lined with stately ailanthus trees, now all but gone, ends at a mossy stone wall enclosing a shady park of some thirty acres, in the center of which, riding the crest of a low hill, stands “Berry Hill,” the majestic home of the Bruces.

The completeness of the plantation composition is remarkable. It is even more remarkable that a house of such grandeur should so long have remained almost totally unknown outside the Halifax County area. The reason for this seems to be its remoteness from the other great mansions of the Commonwealth.

In ante-bellum days the Berry Hill plantation comprised over five thousand acres, and included most of present-day South Boston. (A portion of Main Street and Wilborn Avenue once was a Berry Hill farm road!) Its various tracts were acquired partly by James Bruce of Woodbourne, one of the wealthiest men of his day, and partly by James Coles Bruce, his son by his first wife, Sarah ‘Sally’ Coles, daughter of Walter Coles, Esq., of Mildendo.

Their marriage ceremony took place at Mildendo, the old Coles home on the Staunton River near the village of Providence, and was rushed so as to allow the brother of Sally, then on his death-bed, to witness it. James, not having had time to secure a ring, used one borrowed from one of the guests assembled at the mansion to seal the marriage. It is ironic that the lady who loaned the ring that August day in 1799, Mrs. Elvira Cabell Henry, the young widow of Patrick Henry, Jr., would twenty years later become the second Mrs. James Bruce.

James, the founding father of the Berry Hill Bruces, came from an industrious and well-to-do family, beginning with James Bruce, “the Emigrant”, down through George Bruce of Richmond County, Charles Bruce of King George County, and Charles Bruce of Soldier’s Rest, Orange County.

The son of the latter Charles, James built the great family fortune through what was then a very modern medium–a system of chain stores. At the early age of sixteen he left the relative comfort and security of Soldier’s Rest and went to Petersburg, where he began his career in the mercantile house of a Mr. Colquhoun. He easily won the confidence of his employer, and was sent to Amelia County to open a branch store, in which he was made a partner.

After a few years James found that the more remote areas of Halifax County offered far greater business advantages, so he came here in 1798 and began setting up his stores, not only in the county but in the surrounding counties of both Virginia and North Carolina as well, to supply the needs of the rural planters.

To furnish his stores with their wares, Mr. Bruce also operated a series of wagon trains. This was, of course, in the days before water and rail carriers had been brought into service, and when transportation was slow and difficult due to the unimproved condition of the roads.

Mr. Bruce lived in a day when the accumulation of land and of slaves, for the cultivation and care of crops, in particular tobacco, were objects more appealing to planters than trade; and when engagement in the latter was not considered the proper one for a gentleman who could otherwise provide for his family. Thus there was no competition for him and his stores flourished.

He wisely invested his profits in land and tobacco, as well as in other businesses. The late Dr. Kathleen Bruce, family historian and a noted writer, made an exhaustive study of her great-grandfather’s papers, and revealed that between the years 1802 and 1837, James was the owner or dominant partner in, among other enterprises, twelve country stores, several flour mills, a fertilizer-plaster manufactory, a commercial blacksmith shop, several lumber yards, a cotton factory and two taverns. He was also the owner of sixteen plantations comprising many tens of thousands of acres, and nearly a thousand slaves.

One of the original slave quarters at Berry Hill, constructed of stone quarried on the plantation.

His major purchases of tobacco and other crops–wheat, oats, etc.–were made during the War of 1812, when prices in this country were very low. The purchases were stored in his many warehouses until after the war, when they were sold in England and other European countries at tremendous profits.

In his biography of John Randolph of Roanoke, William Cabell Bruce said of his grandfather, James Bruce:

“If tradition may be believed, sagacity, integrity, and an equable temper were the main factors that entered into his success. But a highly developed instinct of prudence seems to have had something to do with it. ‘I am fond’, Mr. Bruce wrote on one occasion, ‘of taking two securities to a bond.'”But Mr. Bruce was successful not just from a financial standpoint. In his own part of Virginia, and indeed wherever he was known, his name was a synonym for integrity and liberality. A contemporary said he was the “justest and most honorable man” he ever knew.

Dr. James Waddell Alexander, in one of his priceless letters, this one to a Dr. Hall, wrote:

“I have just returned from Halifax. My visit was principally to the family of Mr. Bruce, to which I beg leave to introduce you. His house is noted for its hospitality, and presents to the ‘bon vivant’ as great temptations as can be found in Virginia. At Mr. Bruce’s we seldom sat down to table, during the week I spent there, with less than ten strangers.”When he died in 1837 James Bruce was the third wealthiest man in America, his estate being valued at nearly three million dollars. Only John Jacob Astor and Stephen Girard were wealthier. Mr. Bruce stood apart from these men, however, in that he was the first agricultural millionaire in our history. Yet so clearly did Mr. Bruce belong in the same class with Messrs. Astor and Girard that John Randolph once remarked he would not take the bond of either Mr. Bruce or Mr. Girard for eighteen cents!

This typically Randolph statement notwithstanding, James Bruce and John Randolph were close friends, and there is no reason to think that their friendship was in the least diminished by the defeat of the former by the latter in the election for a seat in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-30, in which Mr. Randolph was such a masterful spirit.

Death came to James Bruce in Philadelphia, where he had gone for medical treatment, and as it was impractical to transport bodies such great distances in those days, he was buried in the yard of old St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. (Nearly one hundred years later his great-grandson, Malcolm Bruce, had his remains brought back to Halifax County and interred at Berry Hill.)

The widowed Elvira Cabell Henry Bruce soon left Woodbourne and moved her family to Richmond, where she built a house on fashionable East Clay Street. A hostess noted for her charming and generous hospitality, she gave liberally to charity, both public and private, and was one of the largest contributors to the fund raised for the erection of St. Paul’s Church, “the court church of the Confederacy.” Not only did Mrs. Bruce attend St. Paul’s until her death–she occupied pew 54–the marriage of her daughter Sarah to the Hon. James Alexander Seddon, Secretary of War of the Confederacy, was the first solemnized in the church.

The Seddons lived for a time in the house on Clay Street known as the White House of the Confederacy. It was built in 1818 by Mr. John Brockenbrough, who sold it to James Morson, from whom the Seddons acquired it. Mr. Morson was a cousin of Mr. Seddon, and was married to Ellen Bruce, sister of Mrs. Seddon. Long recalled in Richmond were the gay parties given at the house, with the “lovely Bruce girls” as hostesses.

After Mrs. Bruce’s death in 1859 her house was sold, and among those who occupied it prior to its destruction by fire in 1910 was the Hon. Alexander Stephens, Vice-President of the Confederacy.

In 1830 James Bruce had purchased from General Edward Carrington, nephew of his first wife Sally Coles, the old Coles-Carrington estate, Berry Hill, situated near the court house. The land had originally belonged to William Byrd II of Westover, to whom it was granted in 1728 by the Crown for his services in helping to draw the dividing line between Virginia and North Carolina.

William Byrd III sold the land to Richard Bland in 1751, and he in turn conveyed it to Governor Benjamin Harrison of Berkeley Plantation. Isaac Coles purchased the 1,020 acres, for 800 pounds, in 1769, and willed the estate to his nephew, Gen. Carrington. One source has indicated that Mr. Coles once considered leaving the land to his Bruce relation, but decided against it after concluding that he already had enough land.

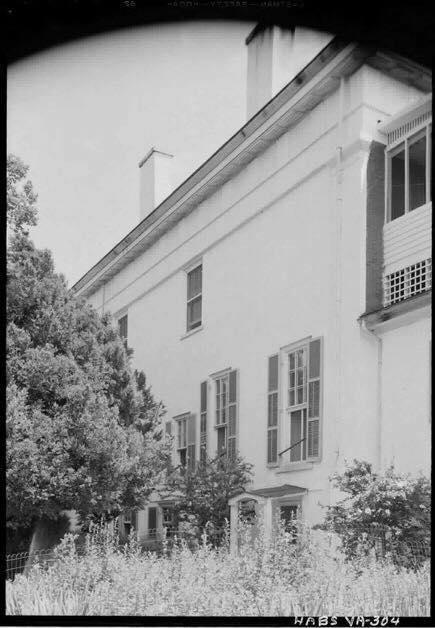

Mr. Bruce gave the plantation to his eldest son, James Coles Bruce, who in 1833 began the erection of the present mansion, an undertaking that was to span seven years. But rather than start from scratch, so to speak, he chose instead to remodel the old Isaac Coles house, built about 1770, that stood on the estate.

A large brick structure, the Coles-Carrington house had one legend attached to it that has persisted over the years. Mrs. Wirt Carrington, in her HISTORY OF HALIFAX COUNTY, stated that it was a belief widely held by his descendants that Gen. Carrington, the son of Judge Paul Carrington, Jr., and Mildred Howell Coles of Sylvan Hill, Charlotte County–the elder Carringtons are buried at Berry Hill–entertained Lafayette in the house in 1824, when the great Frenchman was on his last visit to America, to attend the anniversary celebration of the Battle of Yorktown on 19 October.

(Editor’s note, Shaw, 2005: The legend is not factual. Lt. Colonel Edward Carrington, who served under General Nathanael Greene during the War of American Independence, died in 1810 and was buried at St. John’s Churchyard in Richmond. Col. Edward Carrington’s oldest brother Judge Paul Carrington, Sr. had a son, Judge Paul Carrington, Jr. Paul, Jr. lived at Sylvan Hill at Saxe and had a son named Edward who owned the Berry Hill property. Edward Coles Carrington – 4 Jan. 1789 -1855 – inherited 69 slaves and other property from his uncle Isaac Coles. He represented Halifax County in the Virginia House of Delegates 1819-20. Lafayette, on the other hand, passed through Halifax, North Carolina, in February of 1825 on his way to Raleigh. There is no record in his memoirs of ever coming to Halifax County, Virginia. Lafayette arrived at the October 19 Yorktown celebration having come from Washington on the 16th.)

Because of their close friendship, the legend goes, the General gave for Lafayette an “entertainment” that lasted all night and cost him nearly $10,000. In those days this was a princely sum, and the expenditure, coupled with heavy losses in several business ventures, forced him to sell the land which his uncle had referred to in his will as “my Dan River estate.” Mr. Carrington remained in the county until 1841, when he moved his family to Mississippi and set up a law practice.

The previously mentioned Dr. Alexander, at the time of his visit to James Bruce at Woodbourne is 1827, also spent a few days with the Carringtons at Berry Hill. In the same letter to Dr. Hall, he wrote: “I visited General Carrington, who has a seat on the Dan River, which with the Staunton forms the Roanoke. He is a scholar and a gentleman, and has large possessions. He is a useful, public-spirited man, admired and appreciated by his constituency.”

James Coles Bruce chose the Greek Revival style for his home, even though its popularity was being overshadowed by the approaching Gothic period. Its Parthenon-like facade is a near duplicate of the Second Bank of the U. S. in Philadelphia, which he must have seen when he visited in that city around 1830, so it is natural to assume he was influenced by it.

He was aided in working out the plans for the remodeling of Berry Hill by John E. Johnson, the great architect of the Gothic period who fifteen years later would design Staunton Hill for his half-brother Charles Bruce. A close family friend, there is evidence in the Bruce papers that Mr. Johnson may have lived in Halifax or a nearby county. He and his wife were frequent visitors at Berry Hill as late as 1850.

The architecture of Berry Hill is pure Doric, with a perfectly proportioned pediment upheld by eight massive columns of brick, stuccoed and fluted. The three foot thick walls of the mansion are likewise of stuccoed brick that was made on the place. Rather to say three walls–the back of Berry Hill is not stuccoed. The fully developed entablature carries around the four sides; why the back was left bare has never been known. Yet because of this it is possible to see the brickwork of the original 1770 house, of which the entire back wall is thought to be a part.

Granite for the floor and steps of the seventy foot wide portico and for the window sills came from the plantation quarry; while that which frames the doorway is of a much finer quality and was imported from Georgia.

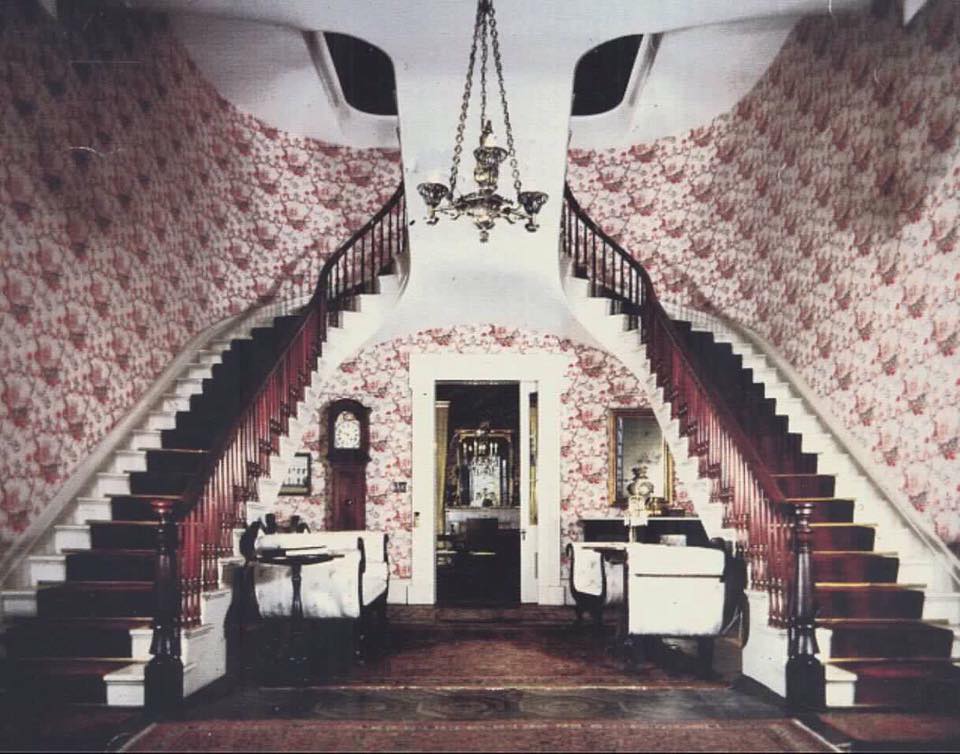

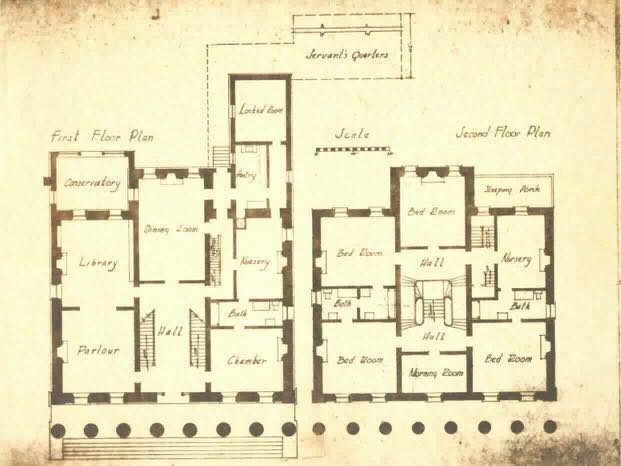

Erected by slave labor at a cost of nearly $100,000, the mansion contains seventeen rooms and a great entrance hall, the latter dominated by a breathtakingly beautiful mahogany “horseshoe” staircase, acclaimed by the late Dr. Fiske Kimball as one of the finest stairs in this country. Two separate flights rise along the side walls to a landing at the back of the hall, where they join and sweep upward over the hall to the second floor. The lack of visible support for the stairs has puzzled architects for decades, and one wonders how it could have been built by plantation artisans without trained help.

Then, as now, quiet luxury best described the interior of Berry Hill. The mantels in the ten major rooms are of imported Italian marble; those in the parlor and library are very elaborately carved, with caryatides supporting the shelves, and show a very strong French influence.

Marble baseboards, ornate plaster ceilings and cherry floors vie for attention with furniture of mahogany and walnut, in styles ranging from Chippendale to Victorian. The only original wallpaper remaining, that in the dining room, is a stunning flock design in olive and gilt, and was imported at the time of the remodeling. Bruce family portraits and paintings grace the ample walls, and Bruce books line the library shelves.

The main floor rooms are large and high-ceiled, while those upstairs are somewhat lower. The second floor claims the single most interesting room in the mansion–the morning room. Overlooking the portico and spacious lawn, the ladies of the house could sit here and sew and still see guests approaching on the ailanthus drive.

James Coles Bruce was a man of exquisite taste, so it was only natural that silver would play a large role in his home. During the Bruce occupancy the mansion was noted for the extraordinary collection of silver housed within it. Besides the usual candelabra, coffee services, flatware and serving pieces, there were plates, goblets, finger bowls, and such; and massive washstand sets of the precious metal in every bedchamber. A large portion of the silver thought to have been designed by Mr. Bruce himself.

The Bruces are gone now, and with them nearly all the silver, but it remains in every room in the form of plated hardware on doors, windows, and blinds, and on the small round bell pulls, tarnished now from lack of use.

The mansion is flanked by the plantation office and the billiard parlor, four-columned miniatures of the “big house” that face each other across the wide, circular drive. They, too, are original, having been built in 1770, and remodeled.

The Billiard Room at Berry Hill is one of two four-columned miniatures of the “Big House” which flank the mansion on each side of the wide, circular drive. Like parts of the mansion itself, they, too, are 200 years old in 1970. Note mounting block in right foreground.

Connected to the back of the main house are a glass walled conservatory, built at ground level to allow for the growth of the large plants the Bruces so loved, and the colonnade containing the house servants’ rooms. A dozen or so dependencies, including the smoke house, ice house, ash house and stables, are in and around the back yard.

The vast grounds are shaded by a variety of trees, some of which have been estimated to be over 500 years old. Fine specimens of boxwood, both dwarf and tree, abound. Mrs. Alexander Bruce once sold slips from the magnificent hedge of tree box in the lower yard, above the cemetery, for several hundred dollars, quite a sum at the turn of the century! It is unfortunate that the finest of the tree box, that which lined the drive between the mansion and the billiard parlor, was destroyed about a decade ago.

The gardens laid out in the early 1840s under the direction of Mrs. James Coles Bruce, covered about six acres, and stretched eastward from the mansion toward the cemetery. The large greenhouse was behind the office. As many as forty slaves at a time were required to maintain them, supervised by Mrs. Bruce and her gardener, a Mr. Graham.

Arranged on three terraces, the various beds were separated by cedar hedges and by gravel walks sixteen feet wide. Foreign as well as native flowers, many varieties of roses and shrubs, and lots of evergreens abounded. Every tree had something planted beneath it to bloom in spring.

After the Civil War, Alexander Bruce, then master of Berry Hill, felt it would be impossible to maintain the old gardens as his late mother would have wanted them, so he had nearly all the plantings removed and the area converted to grass. Luckily, though, the fine boxwood hedges and the aged lilacs encircling the lawn just inside the stone wall were not disturbed.

The family cemetery is located about 500 yards east of the mansion in what was a corner of the gardens. In its thirty graves rest six generations of the Carrington and Bruce families.

Just to the side of the River Road entrance to Berry Hill, in the midst of aged ailanthus trees, is the original overseer’s house. With its quaint windows, and two separate front entrance doors, the house dates, like Berry Hill itself from about 1770.

About two miles away, on the road to South Boston–the Berry Hill Road–stands the Berry Hill Church, built about 1900 by Mrs. Alexander Bruce to replace an earlier one built in 1840 by James Coles Bruce and torn down by her husband because the colored people were no longer attending it. A talented Negro carpenter, Willie Bowmer, drew the plans and supervised the construction of the new church. It was attended sporadically by the white tenants until 1949, when the Bruces deeded it to the local Presbyterians.

During the slavery era Berry Hill plantation was maintained by the Bruces in a highly productive state. Domestic supplies of almost every kind were produced in abundance, yielding in some years, in addition to great quantities of wheat, oats, hay and livestock, between four and five thousand barrels of corn and more than a million hills of tobacco.

James Coles Bruce, born at Woodbourne in 1806, attended both the Universities of Virginia and North Carolina before graduating in 1824 from Hampden-Sydney College. His father had served as a Trustee of Hampden-Sydney from 1805 to 1830, and his step-mother’s grandfather, William Cabell,Sr., of Union Hill, in Nelson County, had been one of its charter Trustees.

Very active in the affairs of his native county, he was a member of the Virginia General Assembly of 1832 which came within a few votes of abolishing slavery in the state. As the largest slave-owner in America–he reportedly owned nearly three thousand–Mr.. Bruce voted against the measure which would have brought about emancipation on a gradual basis.

When he returned home he was quite surprised to learn that some of the other slave-owners of Halifax County had not approved of his negative vote.

Years afterward Mr. Bruce expressed extreme regret that he had voted for the perpetuation of slavery in 1832. In a speech in Danville, which attracted considerable attention at the time, he declared that the greatest harm of slavery was to the white people, not the blacks, as the institution “cheated the planters with a semblance of wealth.”

James Coles also represented Halifax in the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861, where he served with distinction on the very important Federal Relations Committee. In the early days he was opposed to secession, but when Lincoln issued his first call for troops he voted to break with the Union. Thereafter his personal contributions to the Confederacy amounted to more than $150,000.

On 28 March, 1865, while the fighting around Petersburg was signaling the beginning of the end for the South, death came to James Coles Bruce in his chamber at Berry Hill. He was buried in the family cemetery beside his beloved wife, Elizabeth Douglas Wilkins Bruce. The daughter of William Wyche Wilkins and Elizabeth Judkins Raines Wilkins of Belmont, Northampton County, North Carolina, she had preceded him in death in 1850.

(It is interesting to note here that on 12 June, 1865, Alexander Bruce, as executor of his father’s will, paid Thomas Fox of Halifax $50 for his walnut coffin.)

James Coles was deeply devoted to his wife, and her death had left a great void in his life. Several years afterward he told his sister-in-law Mrs. Sara Seddon Bruce that he knew the dead never came back to earth. Night after night, he said, he had thrown himself on her tomb and implored her to return to him, but that return she never did.

While on his death-bed Mr. Bruce said that he felt a rather grim sense of satisfaction in leaving the world at that particular time, as he knew that nothing but ruin was in store for his class.

The war which he saw as the death-knell for Virginia’s slave-based aristocracy reached Berry Hill in several ways. When it was learned that Union troops were approaching the county, a movement that ended in the little-known encounter call the Battle of Staunton River Bridge, Mr. Bruce and his family excepting his son Alexander, evacuated the plantation.

Alexander Bruce, who had studied at Virginia Military Institute under General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, served for a time in the Confederate army, but was released to return home and manage the plantation. The South was just as in need of food for the troops as it was for troops themselves. He along with other men and boys, helped to defend the vital railroad bridge on 25 June, 1864, in the only battle ever to take place on county soil.

Two of Alexander’s brothers did fight in the war, and both gave their lives for the Confederacy. Charles, a captain, was killed in the Battle of Malvery Hill, and Thomas a lieutenant, died in September of 1861 at his home, Tarover, near Berry Hill, of a disease contracted early in camp.

The great silver collection was buried deep in the woods on the plantation, and when James Coles tried to tell Aleck Bank the faithful old butler, its location, he asked not to be told, saying that he did not want to be unfaithful to his master, nor did he want to have to lie about it. “Uncle” Aleck was, however, ordered to burn the mansion if Union troops should come and try to occupy it. A small band, under the command of a General Merritt, did come, but it was said they made no attempt to gain entry. Following the surrender, Gen. Merritt was for a time stationed at Berry Hill.

That the troops made no attempt to enter Berry Hill is not to say that they did not enter other buildings. One of them, caught raiding a Negro’s hen house, was struck on the head with an axe and killed. As he was under orders not to disturb the buildings, no action was taken in regard to it.

When the troops left they took several horses, among them James Coles’ favorite mount. When he returned and learned of it, he immediately dispatched an indignant letter to Gen. Merritt expressing his great surprise at the theft. A few days later the horse was returned to Mr. Bruce, along with a letter of apology from the general.

More troops came before the end of the war, and more of the horses were taken. This fact is affirmed by Alexander Bruce in a letter to his uncle, Edmund Wilkins of Belmont, dated 18 September, 1865:

“We are slowly recovering from the damage done us by the Vandals. Our greatest loss was in horses, not one being left on the plantation with the exception of a refractory mule, which they were unable to catch after repeated trials.”Alexander Bruce succeeded his father James Coles as master of Berry Hill, and under his direction, though the tenant system was then in effect, the plantation continued to run smoothly, if not prosperously. There were many years when he barely broke even, and some when he did not do even that well. Tobacco and grain continued to be the most profitable crops, due in large part to the richness of the land, in particular the Dan River low grounds.

A word here in regard to the emancipation of the slaves. It speaks well for the treatment they had received at the hands of the Bruces that, after the war, none of them left the estate. All elected to remain and work for wages.

A rare insight into life at Berry Hill in the decade immediately following the Civil War has come to us thought the diary of a young Albemarle County girl, Anne Nelson Page, who was, in the fall and winter of 1873, tutor to the children of John Clark of Millwood and Banister Lodge. With the Clarks she visited Berry Hill on 13 December, and recorded the highlights of the afternoon in her diary:

“When we got up this morning it was very cloudy and windy and began to rain fast soon after breakfast…We went to Berry Hill about two o’clock in the pouring rain…We had a very pleasant day; Mrs. Bruce is such a nice lady, and the house is beautiful with handsome carpets, mirrors, pictures, etc…We played Authors, of course, as that game seems to be all the rage up there…Dinner was announced about 31/2 and was a very welcome sound, as I was playing the piano and did not object to an interruption. I must describe the dinner next: soup out of SILVER PLATES, turkey, oysters, sausages, tomatoes, and every variety of vegetables and SILVER GOBLETS to drink water out of and glass for the wine, of which I did not partake. The dessert was custard, cake, blanc-mange, preserves, and apples, and wound up with SILVER FINGER BOWLS! I never felt so fine in all my life. “After dinner we went out to the billiard room where Mr. Bruce and Mr. Tom were playing. It had cleared off beautifully then and we left about dark…going back to Tarover…”Alexander Bruce died 5 October 1906, leaving Berry Hill to his children. Walter Coles left college and moved to Alabama, where he dealt in real estate and served as manager of Bell Telephone Company in Montgomery. Ellen Douglas married Richard Crane III, an heir to the Crane plumbing fortune and at one time U. S. Ambassador to Czechoslovakia. The Cranes lived at Westover, the home of the Byrds, that is now owned by their daughter, Mrs. Bruce Crane Fisher.

Malcolm Graeme Bruce, the last of the Bruces to live at Berry Hill, was twice married. He and his first wife, Myrtle Heisen, a Chicago heiress, lived in Richmond, where he practiced law. She died in 1916 and was buried in Hollywood Cemetery. Several years later he married his cousin, Betty Bruce Williams, of Culpeper, and with her returned to live at Berry Hill. The second Mrs. Bruce died in 1943.

Following the death of Malcolm Graeme in 1948, Berry Hill was sold to Mr. Frederick E. Watkins of South Hill and Richmond. Included in the sale, along with the mansion, were family portraits and furniture, plus 2400 acres of land.

An aged Negro caretaker, Richard Cecil Rogers, lived in Berry Hill for a number of years, but since his death several years ago the mansion has been unoccupied. And as with every house unoccupied and unloved, Berry Hill is fast beginning to show its age. Time and the elements play no favorites.

The family cemetery, still owned by the Bruces, recently received some much needed attention in the form of a general cleaning-up. Afterward, at this writer’s suggestion, four of the crypts, those of Paul and Mildred Coles Carrington, James Bruce and the child of a Berry Hill overseer, were restored. All this work was sponsored by Mrs. Myrtle Bruce Shipman of Smyrna, Delaware, daughter of Malcolm Graeme Bruce, and Mrs. Fisher of Westover, Charles City, Virginia, daughter of Ellen Bruce Crane.

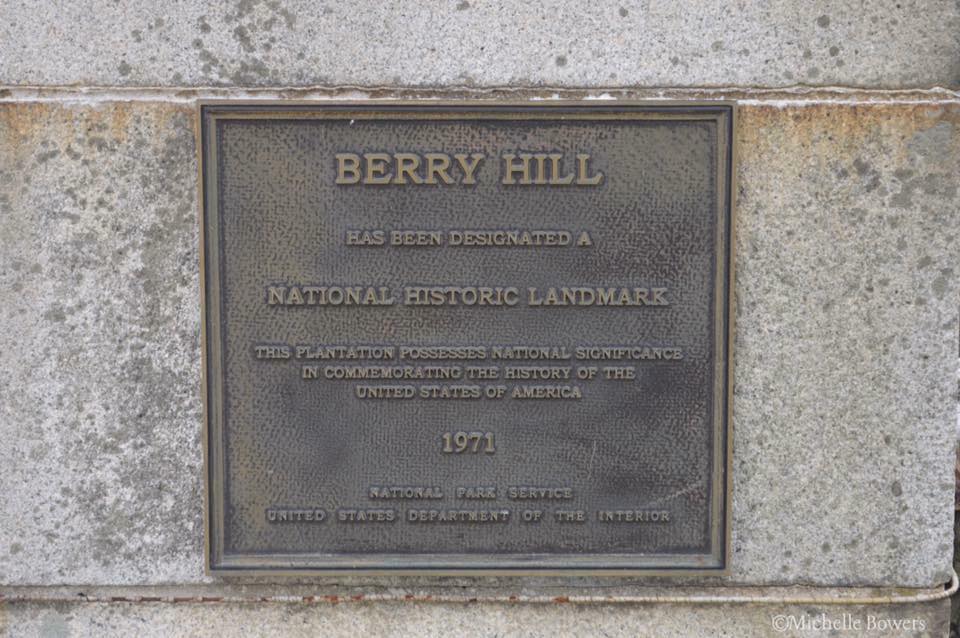

Justly acclaimed as the finest example of domestic Greek Revival architecture in the United States, Berry Hill was chosen in 1968 for inclusion in the book, Architecture in Virginia, commissioned by then Governor Mills Godwin. The reasons given for its selection are appropriate here:

“Berry Hill was almost the last of the great houses to be built in Virginia…Its isolated site lends an almost overpoweringly romantic aura to the distinction of its carefully executed portico flanked by two small Doric pavilions. The entire composition is on as grand a scale as any of Virginia’s domestic architecture, with the possible exception of the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg. It is a notable achievement, particularly when one realizes that it was carried to completion in a remote area of the Commonwealth. This isolation gives the entire composition as almost theatrical air of romanticism, in spite of the classic forms of the three buildings that frame the forecourt.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For the help they have given me in the writing of this article of Berry Hill, I extend special thanks to the following:

MRS. MYRTLE BRUCE SHIPMAN, who provided me with many historical facts, read the article and offered suggestions of it; MISS ANNE PAGE BRYDON, of Charlottesville, for permission to quote from the diary of her grandmother, Anne Nelson Page later Mrs. Nathanial Ragsdale Coleman of Riverside, Halifax County) and DR. HENRY WILKINS LEWIS, of Chapel Hill, N.C., who provided facts on the family of Mrs. James Coles Bruce, and granted permission to quote from the letter from Alexander Bruce to Edmund Wilkins.Special thanks are due MR. AND MRS. MORRIS T. ROYSTER, overseer-caretakers at Berry Hill. Over the past several years they have extended every courtesy to me. They are indeed friends.

This article is was originally published in The Record-Advertiser, December 17 & 24, 1970, by Kenneth H. Cook,

and provided by The South Boston-Halifax County Museum of Fine Arts and History

For comments, suggestions or inquiries, email the Webmaster of Halifax.Com.

This page was last updated on June 23, 2005.