Written by Bill Harris

In 1860 North Carolina’s population included 30,463 free blacks out of a total population totaling close to one million, including 331,059 slaves. According to John Hope Franklin, author of The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860, most free blacks were located in eastern rural North Carolina. Some were able to purchase their freedom, others were freed by their masters and some managed to simply escape their life of bondage. This segment of North Carolina’s population had grown significantly since 1790. In that year only 5041 free blacks were in the state.

Franklin County, by comparison, had fewer free blacks than other counties in the area. According to the 1860 census, Granville County had 1123, Nash had 687, Wake had 1446, Halifax had 2452 while Franklin County had only 566 free blacks. Only Warren County had fewer with 402 free blacks. Most of the free black population were engaged in farming, but some owned land and others were craftsmen. These craftsmen included carpenters, blacksmiths, stone cutters/masons and coach builders.

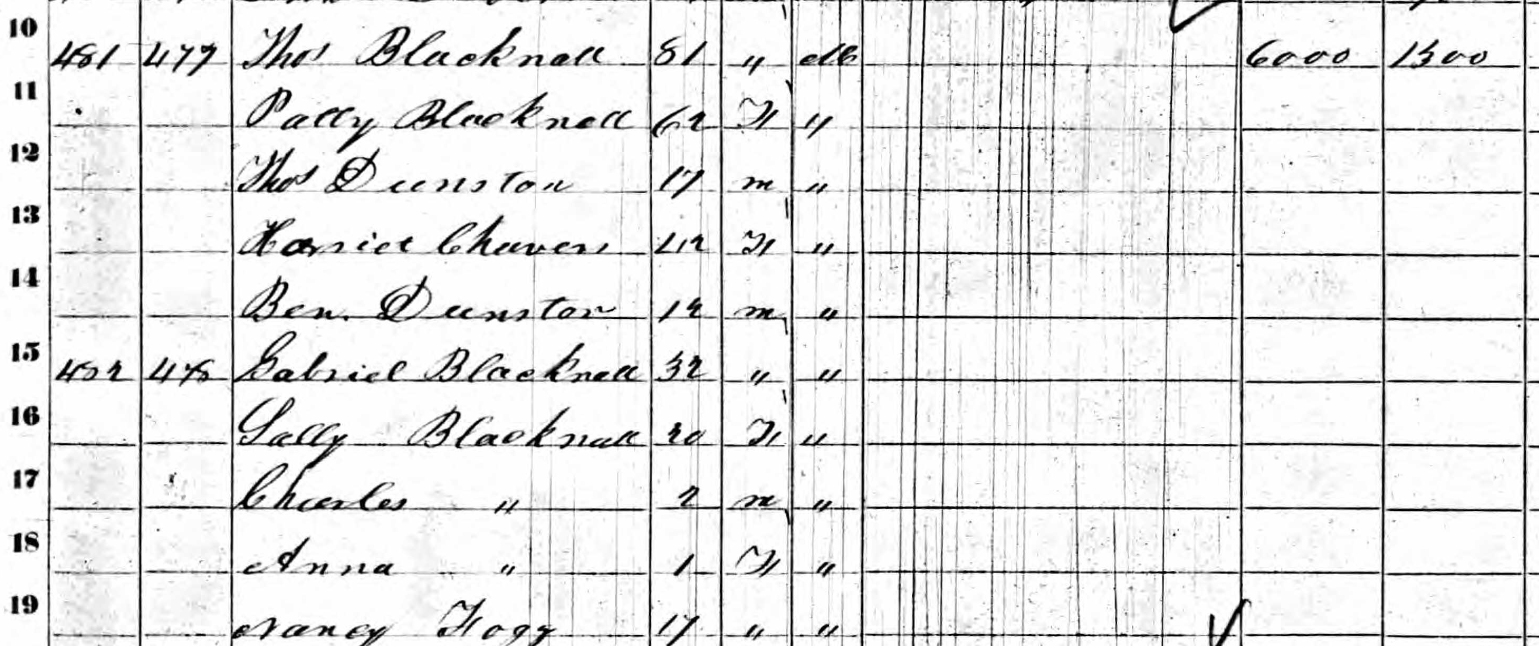

According to Dr. Franklin, only two of Franklin County’s free blacks owned slaves. One was John Hogwood, who owned one and the other was Thomas Blacknall, who owned three. It is interesting to note that on the 1860 census, Blacknall is listed as mulatto but on the 1850 census he is listed as black. By 1860, Blacknall was was one of the wealthiest free blacks in the state. It is estimated that Blacknall had real estate valued at $6,000 and a personal estate worth $1,300. To put that in context, a value of $7,300 in 1860 would be almost $260,000 in today’s money.

Additonally, in 1830 Blacknall owned seven slaves and had significant property holdings along Lynch’s Creek in the Rocky Ford area of Franklin County which he had purchased in 1823 and then added to this in 1836 when he purchased additional property.

Local historian Maury York wrote about Thomas Blacknall recently for an article in the Franklin Times. According to Mr. York, Blacknall was freed at the age of 42 by James Houze. Houze had acquired title to Blacknall from representatives of Thomas’ previous owner, William Blacknall.

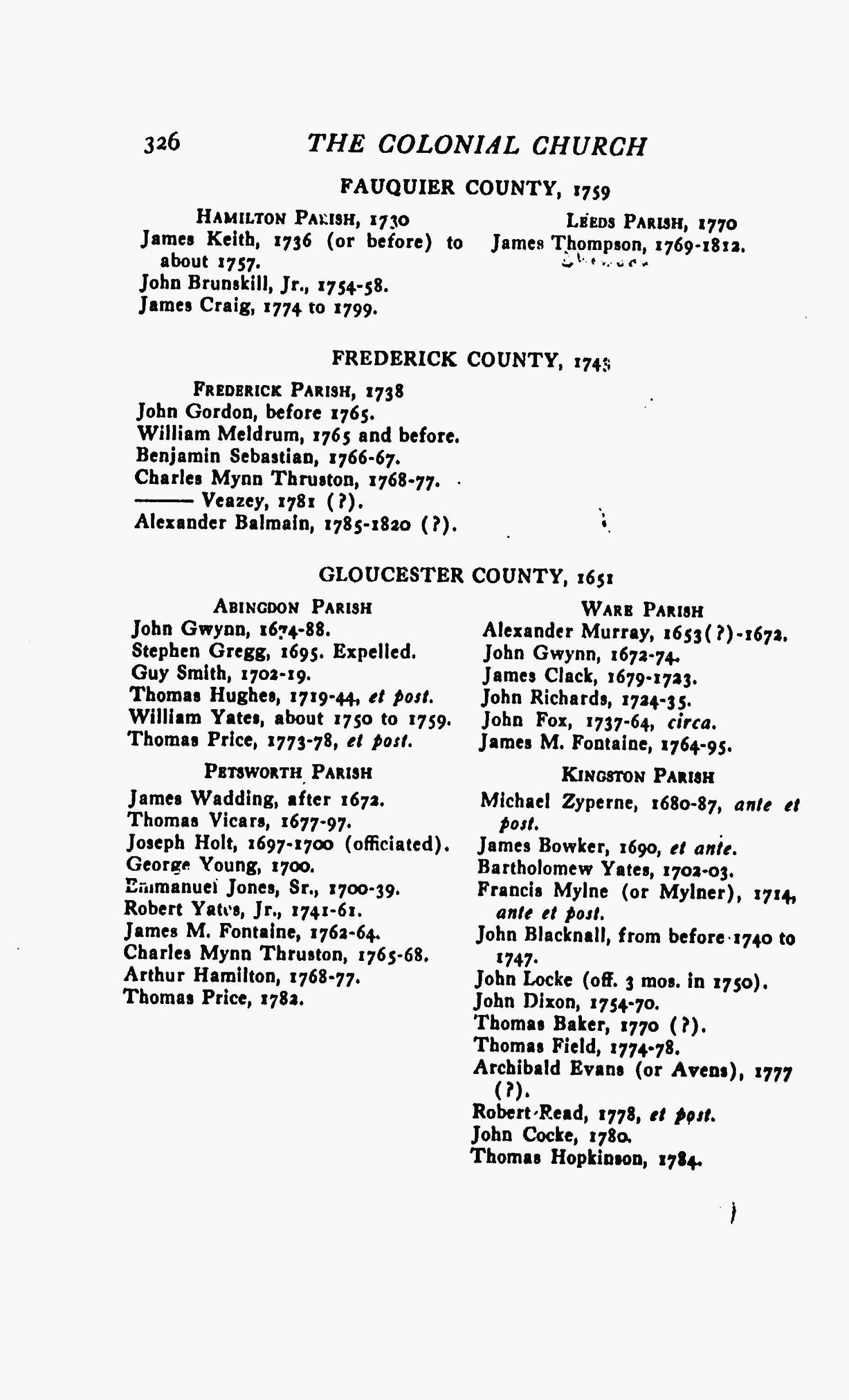

Before we continue on with Thomas Blacknall’s story, let’s take a quick look the family of William Blacknall. The Blacknall family had come to America in July of 1726. Rev. John Blacknall arrived in Edenton, NC and soon found himself in Gloucester County, Virginia preaching the gospel.

Like so many other families in the Gloucester/Mathews County area of Virginia, the Blacknall’s moved to the Granville/Warren/Franklin area of North Carolina. According to Carrie Blacknall, a great-grandaughter of Rev. Blacknall, it was Rev. Blacknall’s grandsons, Thomas and John who moved here.

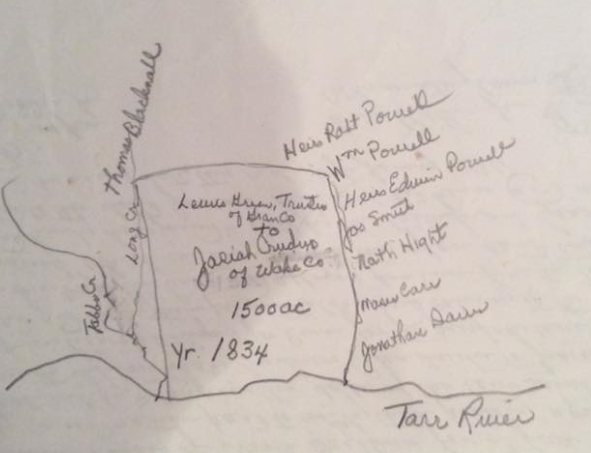

Thomas bought a large tract of land about a mile from Kittrell, bordering the Josiah Crudup property on the north side of the Tar River, while his brother John bought property on the south side of the Tar.

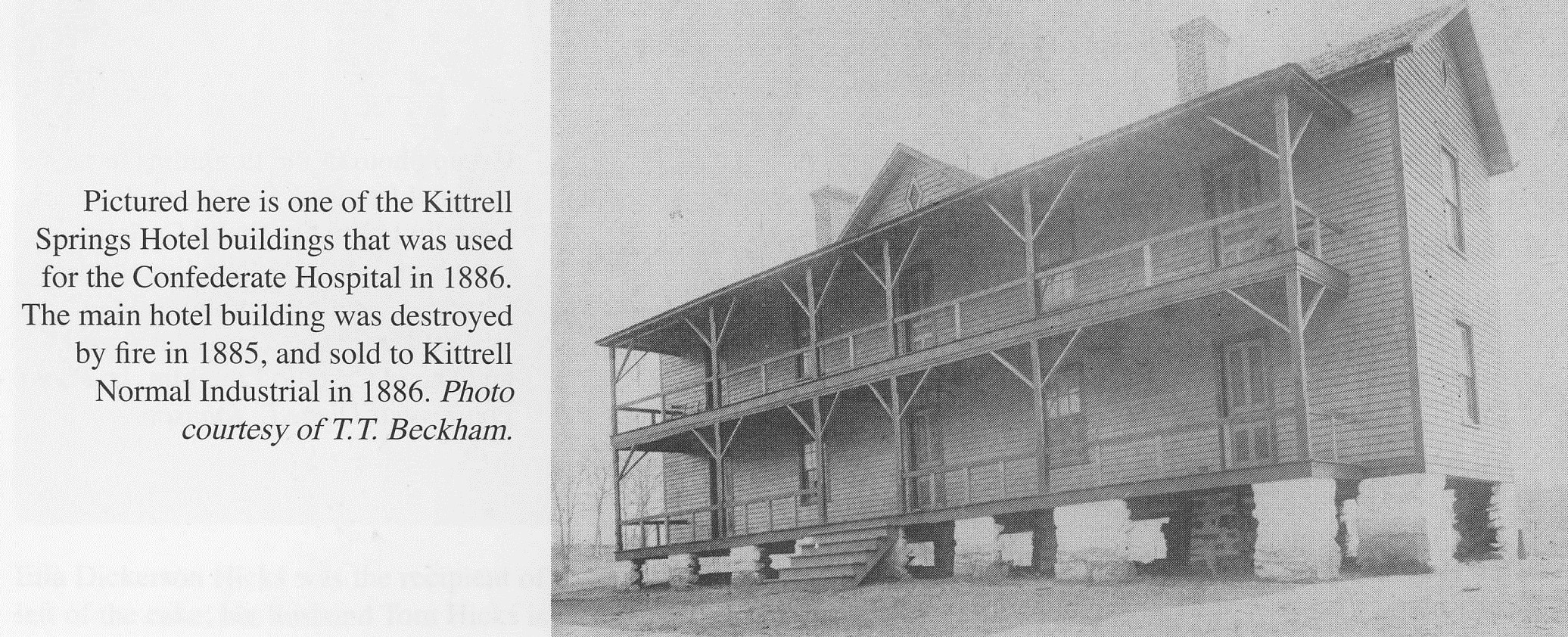

John Blacknall was born in 1753 and died in 1812 and he married twice, first to Margaret Jarvis, who died in 1798 and, secondly, to Elizabeth Blacknall. Between these two marriages John had 11 children. William Blacknall was one of these eleven children and the oldest, born in 1790. Many of the Blacknalls were well known. They owned Kittrell Springs hotel, which was later turned into a hospital for soldiers in the Confederate army.

Descendants owned the Continental Plant Company.

The Blacknalls also owned many fine houses throughout the area such as Blackenhall and Beech Springs. These houses, unfortunately, no longer stand. The Blacknalls suffered many tragedies but were very influential during the 19th century.

William Blacknall was born in 1790 and died in 1816. It was this William Blacknall who, on his death bed, stated his desire to free Thomas Blacknall. Thomas had originally been the property of William’s father.

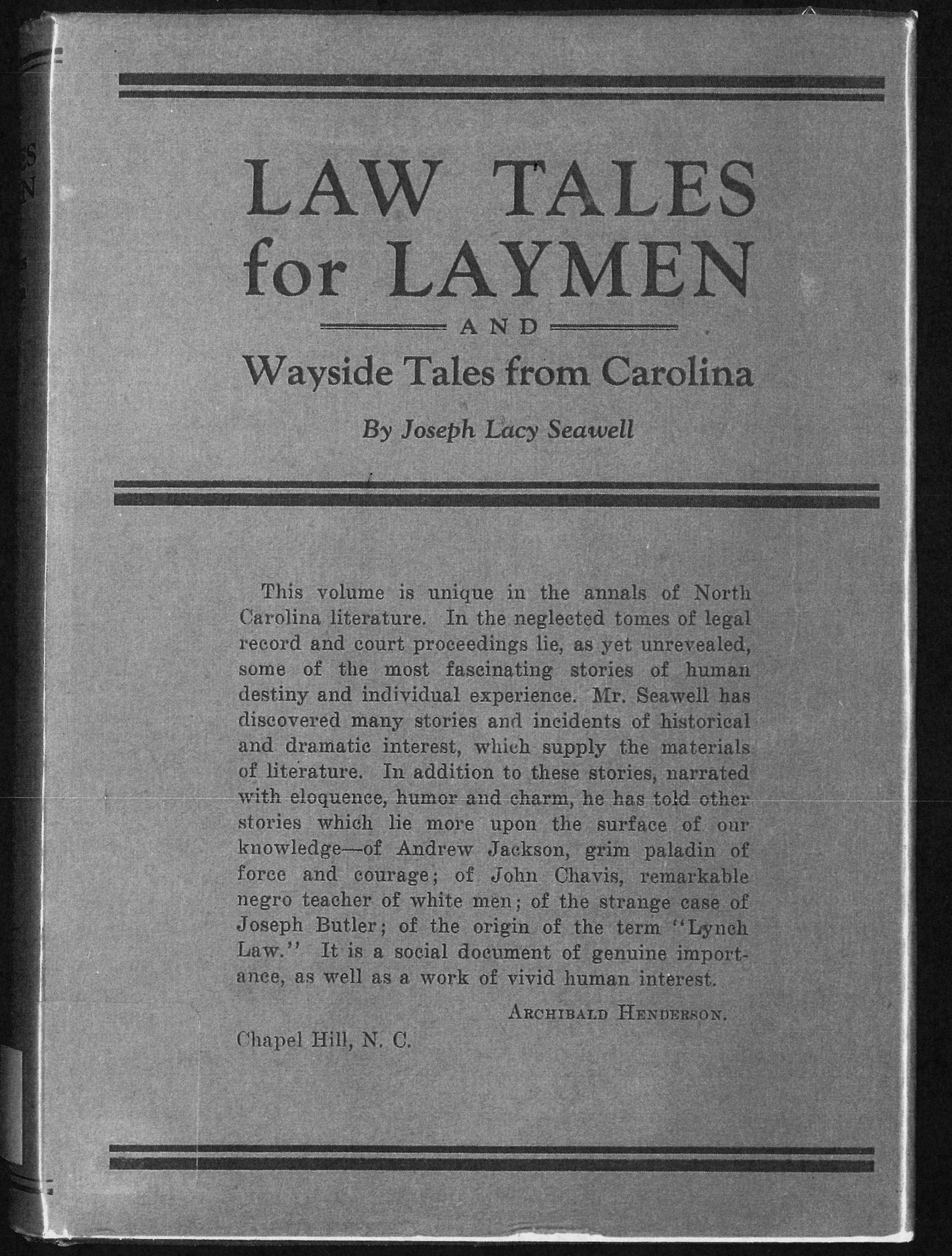

According to the 1925 book, ‘Law Tales for Laymen: Wayside Tales of Carolina’ by Joseph Lacy Seawell, Thomas Blacknall was known as the chattel of John Blacknall. Seawell states that Thomas Blacknall was born on John’s plantation in Granville County (remember at this time, Vance County did not exist so this plantation, which would now be in Vance was, at the time, in Granville County). However, the 1860 census shows that Thomas Blacknall was 72 years of age and was born in Virginia. It is certainly possible he was brought here from Gloucester Co. when John moved here. In any case, Thomas Blacknall was a slave and owned by John Blacknall. Upon John’s death, Thomas became the property of William Blacknall.

According to Seawell, Thomas Blacknall was not only a blacksmith held in high regard for his quality work but was also a bell maker. John allowed Thomas to keep the money he earned from his work and to travel freely as far as Baltimore so he could sell his work and ply his trade. Seawell quotes Thomas Blacknall’s grandson, Rev. John J. Young, who stated that Thomas purchased his freedom for $800. Young further stated to Seawell that, as a slave owner, John Blacknall was entitled to everything that Thomas earned but John not only let Thomas keep his earnings, but supplemented them in order to aid in Thomas acquiring his freedom.

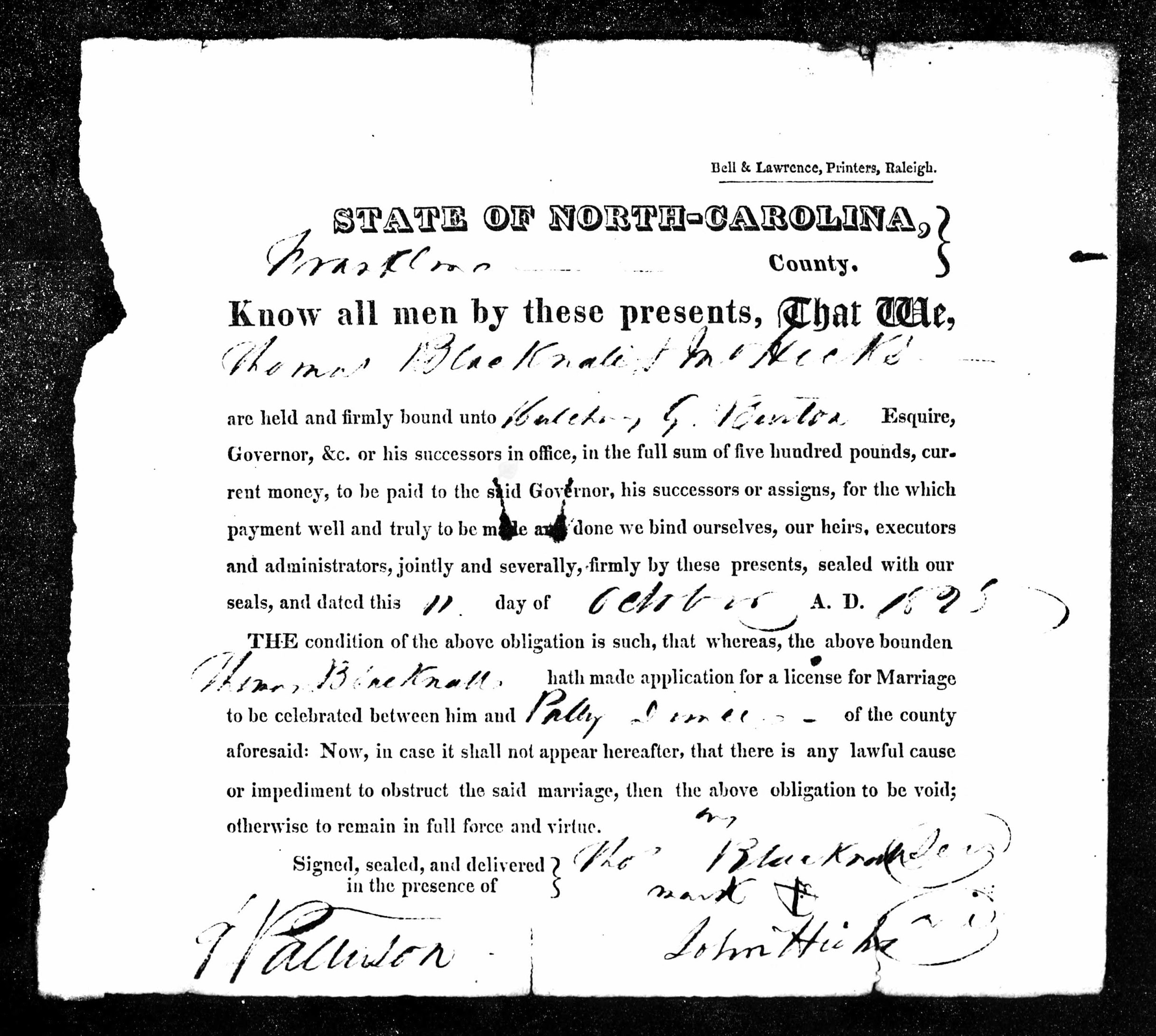

This would seem to be quite a different story than to the one Maury York tells. According to York, it was in April of 1820 that James Houze appeared before the judge of the Superior Court of Franklin County with a petition requesting that Thomas be granted his freedom. This petition states that Thomas had recently belonged to William Blacknall. At the time, state statutes required a bond posting of 100 Pounds which was paid. The court agreed to this petition and freed Thomas Blacknall. So we have two different stories about how Thomas Blacknall obtained his freedom. However it happened, Thomas was a free man at the age of 42.

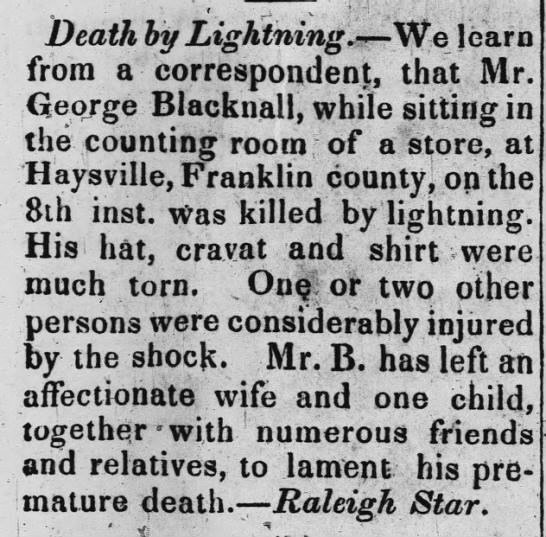

Fortunately for Thomas, he was held in high regard for his work so he had money to buy property and he set about doing just that. According to York, Thomas Blacknall, with assistance from James Houze, bought 175 acres of land from George Blacknall, who was either John Blacknall’s brother or, more likely, the George Blacknall who was John’s nephew and ran a store in the same area where Thomas would have been living.

This property was located on what was then called the Granville Road which would now be the road from the Ingleside community in Franklin County to the Bobbitt community in Vance County. In an 1844 deed, Thomas Blacknall purchased 143 acres on Lynch’s Creek, adjoining property he already owned, for $350 from Robert K. Smith of Chatham County. At some point, Thomas also purchased what was known as the “Toole Tract”. This would have been the property of Geraldus Toole for whom Toole’s Creek is named after.

Geraldus Toole was from Edgecombe County, but had a summer residence of some significance on Toole’s Creek in Franklin County and this property likely adjoined land already owned by Thomas Blacknall. According to Seawell, this property cost Blacknall $1,275. Geraldus Toole died in 1838 and the property passed to his daughter, Mary Lavinia Toole. Mary had married General Joseph B. Littlejohn, a resident of the community that was at the time known as Macon.

Local historian Rev. E. H. Davis, writing in the Franklin Times in 1939 noted that Littlejohn’s home was called Ingleside and was to be the name of the community when it was decided Macon was no longer to be used. This home was located just south of the U.S. 401/N.C, 39 intersection and was destroyed by fire. It would have only been a couple of miles from Littlejohn’s home to Geraldus Toole’s home and to where both of the Blacknall families lived. Many well known Franklin County families made their home in this area including the Macons, Fosters, Seawells, Glenns and so on.

Thomas Blacknall, like most everyone at the time, was religious. In his book, Seawell says that Sallie E. Mitchell, a resident of the area and related to Nathaniel Macon, remembers that Thomas Blacknall was so respected that he frequently led white congregations in prayer at a Presbyterian church in the area and was a deacon at this same church. John J. Young says that later in life Blacknall became a Baptist.

Thomas Blacknall was also a family man. He was married twice. According to Seawell, his first wife was a slave who lived 20 miles away and Blacknall bought her freedom. With her he had at least four sons that Blacknall purchased, effectively making his own children his slaves by title. His second wife was named Patsey. She was free born. Thomas and Patsey Blacknall had 5 documented children: Gabriel, James, Becky, Harriett and Peggy.

According to York, by 1850, Thomas, Patsey and their children were living on their farm with several children and grand children including Gabriel, James and Becky. On the farm, in addition to the blacksmith work Blacknall was known for, they raised wheat, corn, oats and other vegetables. Blacknall owned horses, cattle, sheep, oxen and swine. Three slaves, all over the age of 50 provided labor for the farm. These three slaves may have actually been his sons from his first marriage.

By 1860, Blacknall prepared his will. His wife was to receive all 654 acres of land for her use during her lifetime and this included the Toole tract along with farm animals, household furniture and agricultural implements. His son, Gabriel, would inherit all of the blacksmith tools, a horse, a few farm animals and, after the death of his mother, two slaves: Starlin and Charles. He also described how his acreage was to be divided after the death of Patsey. Grandson Tom Dunce would have 15 acres on the west side of Blacknall’s house tract near Lynch’s Creek and hold it as a home for Dunce’s mother, Harriett, during her lifetime. Gabriel would be the beneficiary of one third of the remaining land while daughters Becky and Peggy would get two thirds split between them. Mary Fogg was also bequeathed a slave named Bob, who may also have been a son from Blacknall’s first marriage.

Gabriel would marry Sallie Ann Fogg, Harriet married a Dunce (this name possibly evolved in Dunston, of which there are many in Franklin County), Peggy married Woodley Hawkins, Becky married Edward Mayo and there is no record of who James may have married that I have seen.

So we can account for many of Thomas’ children, but who is Mary Fogg and why was she given a slave named Bob, who may have been Thomas’ son from his first marriage? Therein, lies a tale. As told by Joseph Lacy Seawell, Bob was one of Thomas’ sons born into slavery from his first marriage. Bob, now held in serfdom by his father, married Mary Fogg. Mary Fogg was the legitimate child of an English soldier who served under General Cornwallis. This English soldier was named Joseph Butler. Butler was injured during the Battle of Guilford Court House in March of 1781. When Gen. Cornwallis retreated to Wilmington, Butler became a straggler and was lost from his command. Apparently, according to Seawell, he was taken in by a free mulatto woman in either Granville or Warren County where she hid Butler until the war ended in October of 1781.

He was nursed back to health by this woman’s daughter with whom Butler became fond of. They wanted to be married, but according to North Carolina law at the time this would be impossible since Butler’s blood was 100% white and the young woman’s was not. He remained on the woman’s farm and took the name of John Fogg while attempting to hatch a plan to circumvent the law so he would be able to marry this young woman. At some point, the young woman became sick. As part of her treatment a blood letting was performed by a surgeon, a common treatment in that time for many different ailments. According to Seawell, Butler (or John Fogg, as he was now known) witnessed this procedure and while it was taking place drank a large quantity of the blood, much to the surprise of the surgeon. The following morning he left and swore an affidavit that he did indeed have African American blood in his veins which allowed him to procure a marriage license. According to the story, the couple were married and a daughter, Mary Fogg, was born to this union and Fogg went on to marry Bob, son Thomas Blacknall and his first wife. It does seem a bit of a tale. Maybe it’s true, maybe not, but it’s a great story.

To add to this, Bob was known as Bob Young. Slaves took the names of their master and when Thomas purchased Bob he was the property of a man with the last name of Young. Bob, after being purchased by Thomas never changed his name to Blacknall. Bob Young and Mary Fogg were the parents of Rev. John J. Young. It’s also not unreasonable to think that Gabriel’s wife, Sallie Ann Fogg, was related in some way to Mary.

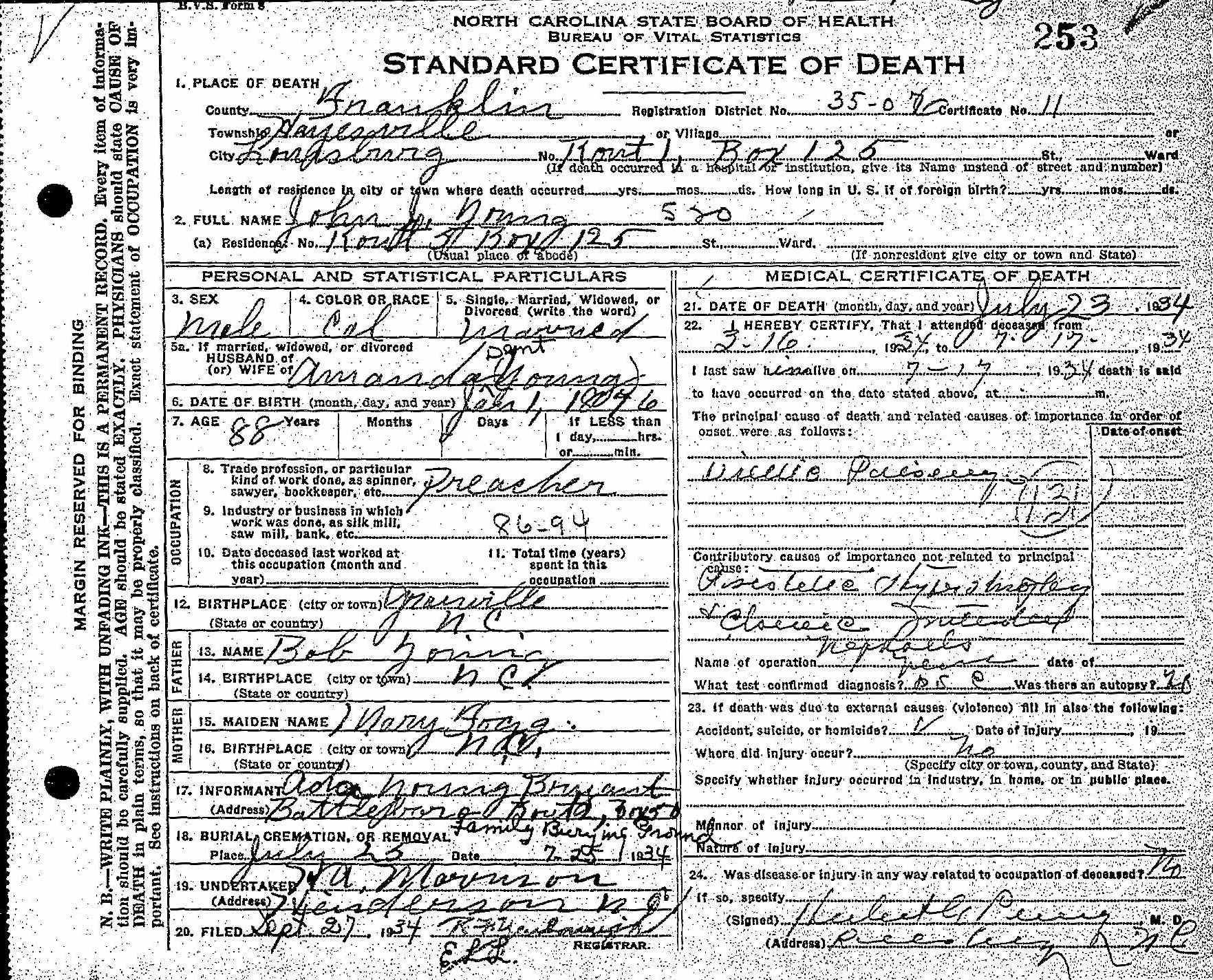

Thomas Blacknall died in April of 1864 at the age of 86. Records do not indicate where his final resting place was located, but if you travel around the Rocky Ford area you will find small burial grounds containing many of his descendants. It is likely that he was laid to rest at one of these small family plots. Gabriel Blacknall is buried at White Hall Baptist Church Cemetery at Rocky Ford. There is no longer a church there but the cemetery remains.

This cemetery contains a number of Thomas Blacknall descendants including Dunstans and Foggs. According to the findagrave.com website, Sallie Ann Fogg, Gabriel’s wife, is buried here. Just across the road from the Whitehall Cemetery is the Hawkins family burial ground. Other Blacknalls are buried here along with members of the Fogg and Hawkins family.

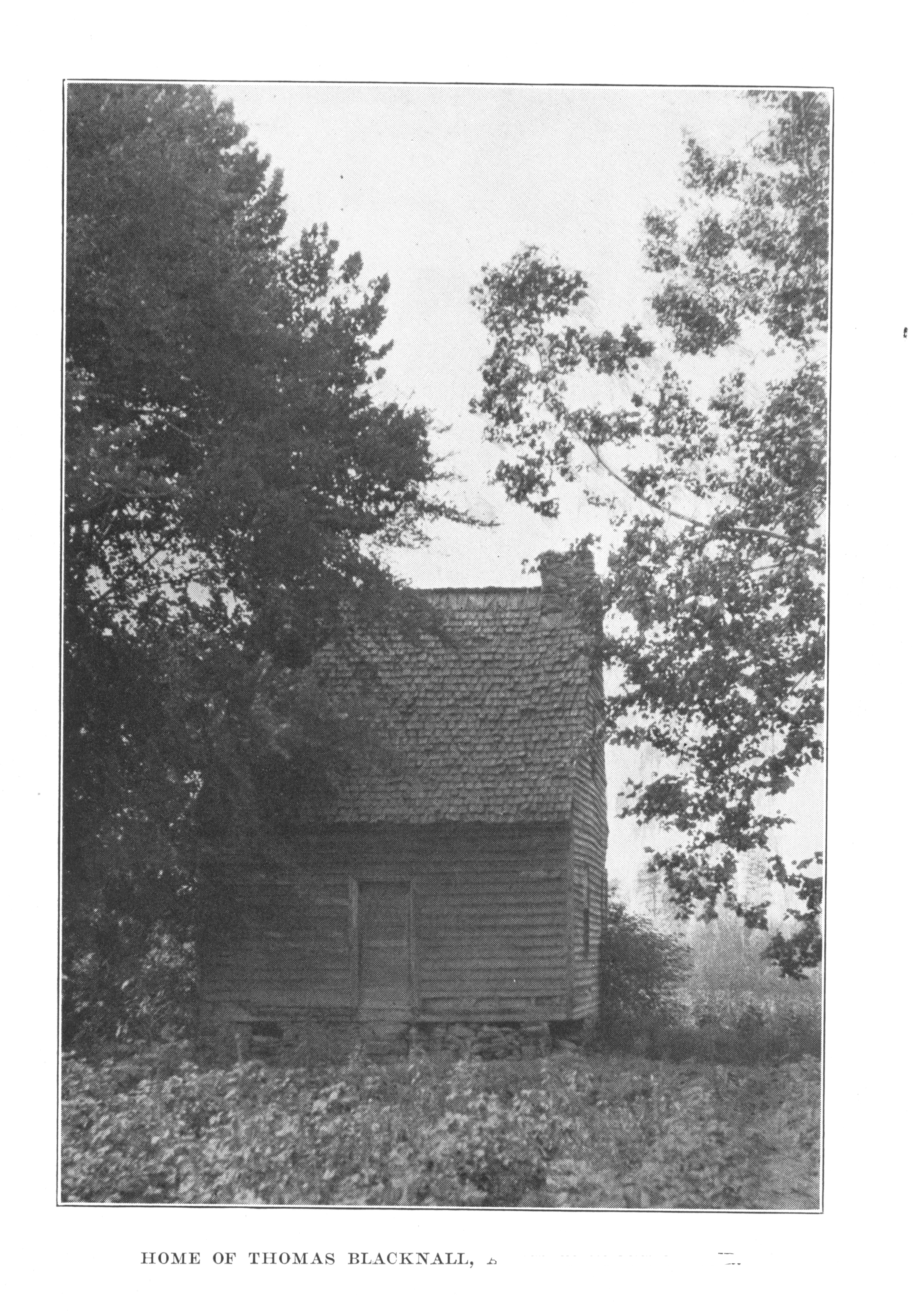

Even though Thomas Blacknall owned the fine home of Geraldus Toole, he apparently never lived in it. According to Seawell, Blacknall lived in a much smaller home. Patsey allowed a grandson to live in the Toole house. After the grandson passed away in 1922 the Toole house, like many other great houses in this area, fell into ruin rather quickly after his death. According to Seawell, the Toole house had beautifully hand-carved mantels and mottled interior decoration.

It appears to have been a fine home for the Tooles and the Blacknalls. According to Jeremy Bradham, Historic Preservation Specialist at Capital Area Preservation, the Thomas Blacknall house “honestly looks like a dependency, but I am aware that it is not. There is one like that in Edgecombe county I believe, or somewhere down east. It’s somewhat vernacular, but just a simple cottage of sorts.”

While certainly not as impressive as the Toole house that Blacknall owned, his own home obviously served him well. Once again we only have the one photo that survives from Seawell’s book. Nor do we know the exact location of either of these houses beyond the Rocky Ford area of Franklin County. It’s safe to assume the Geraldus Toole house was somewhere near Toole’s creek. It’s easy to assume that Thomas Blacknall’s house was close by but we have no proof of that. Certainly it could not have more than a couple of miles from Toole’s house but as to the exact location, we just don’t know. It’s a travesty that neither one of these houses, with their importance to history and architecture of Franklin County, have not survived.

At at time when an entire culture were enslaved, a few men like Thomas Blacknall overcame what might could have been seen as insurmountable odds. Through hard work, a little luck, and a little help along the way, Thomas Blacknall flourished. Setting the groundwork for the success of his many descendants in Franklin County and beyond.

A few thank yous are in order for their help with the preparation of this article: Maury York, former Chairman of the Franklin County Historic Preservation Commission, for allowing access to the articles he wrote for the Franklin Times, Mark Pace for provided the Joseph Lacy Seawell materials, Marilyn Blacknall who, like me, is a descendant of Rev. John Blacknall and is an expert on the Blacknalls and Jeremy Bradham for his architectural knowledge. They have all helped to make this article possible and I thank and appreciate their help.