Written by Bill Harris.

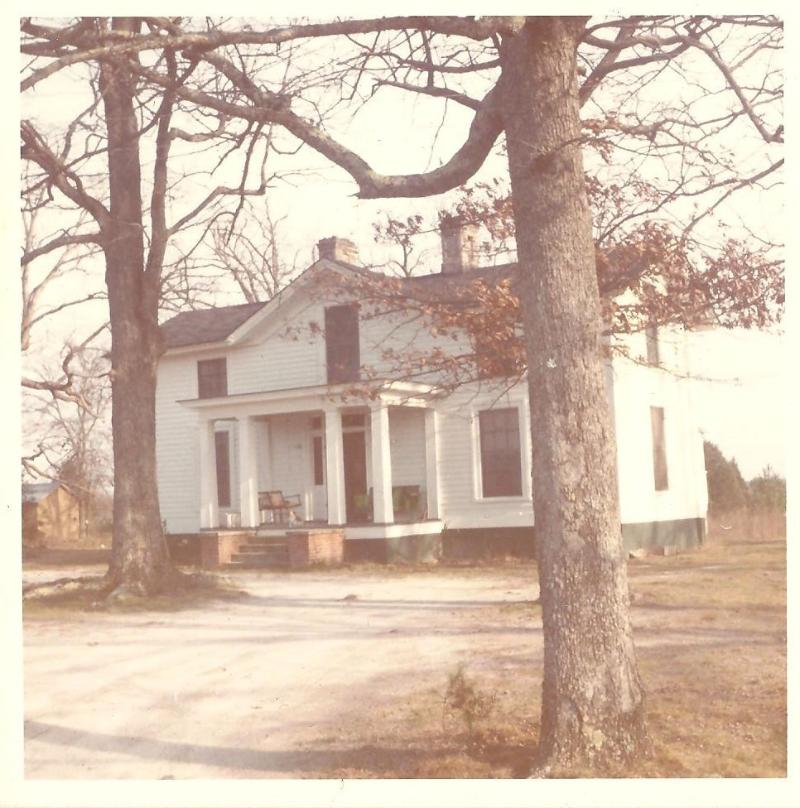

Home. It’s a simple word. It means somewhere you are always comfortable, where you are accepted and where you feel the important events of life more keenly than anywhere else and where we all want to be at the end of the day. Home is a word I didn’t truly understand until 1976. As a kid of the 1960’s and 70’s we moved all over eastern North Carolina. My dad, who was from Pitt County, took jobs all over so we never stayed in one place for too long but when I was 10 in 1973 my father died. After his death, my mother wanted to go home. Home for her was Louisburg. Not just the town, but more specifically, Oak Grove. This was the 1850 plantation house that was probably built by famed Warrenton architect Jacob Holt for my mother’s great grandfather, Dr. Peter Stapleton Foster.

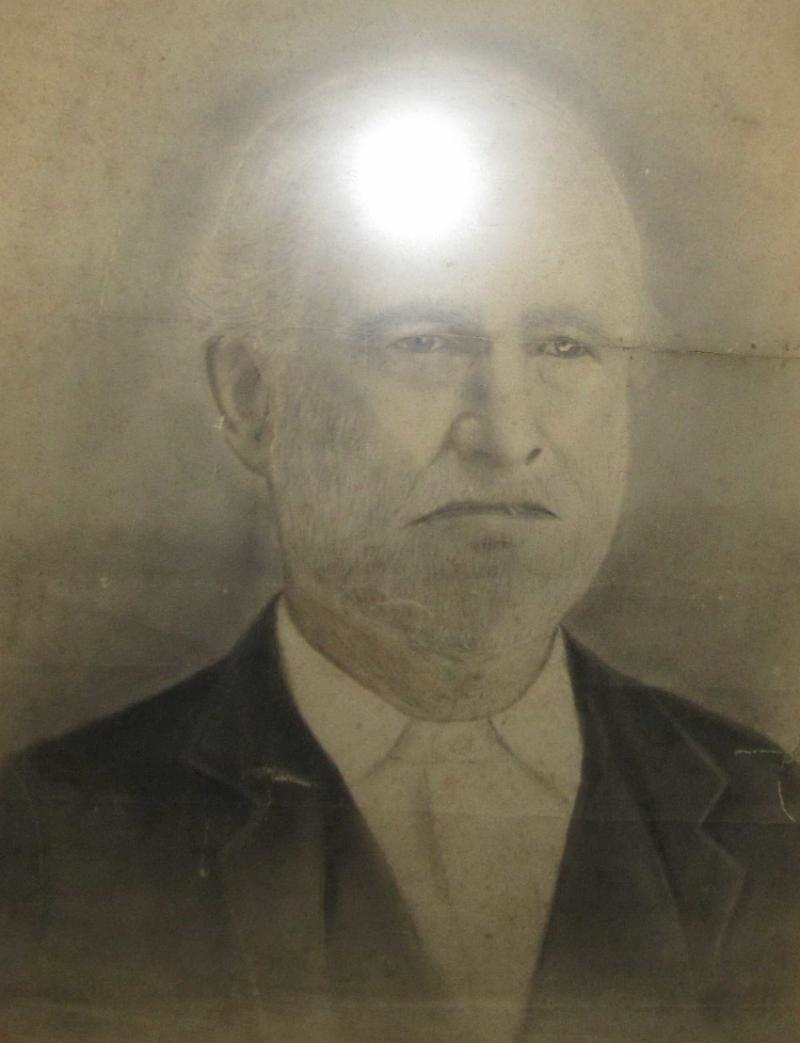

Dr. Peter Stapleton Foster

We never really called it by the name Oak Grove. It was always “out home”. As a child, we always visited “out home” at Christmas or Thanksgiving and once or twice more during any given year. It always seemed like somewhere very far away from where we may have been living and everything about the place seemed old and out of time and it smelled of moth balls.

Oak Grove, Circa 1925

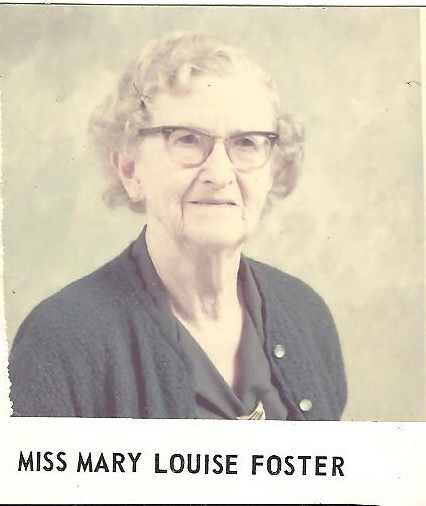

After living in Louisburg from late 1973 to 1976 my mom decided to modernize “out home” and finally return to the place of her birth. I won’t bore you with all of the details of the mid 70’s renovation that took place, but suffice it to say that the house was a bit more livable than it had been. It wasn’t in terrible shape but let’s just say the wood stove was not going to be in use any longer. I remember a day in the early fall of 1976 particularly vividly. I had just gotten off the bus from school. My mother and my great aunt, Mary Louise Foster (we called her “Sister” as she was my grandfather’s sister) sat on the porch shelling peas. My mother said to me that we would have to move. I don’t remember why she said we had to move, only that we would be. I remember beginning to cry. It was at this point my mother told me she was only kidding. She had no idea I would react that way. We had moved so much my mother didn’t think I would have this reaction. But I did because I had found Home. At 13 I didn’t know what connected me to this old house but there was a connection and that connection has grown over the years. It was the first place I lived that I felt I was where I belonged.

We had only been living “out home” for a few months but I had been going there since I was born. Sister and our cousin, Matilda Brown, had lived there. They were two elderly ladies that everyone in the Ingleside area knew and loved. They both seemed perfectly ancient to me at the time. Matilda’s health failed in early 1976 and she went to live with family near Charlotte and that left Sister by herself and at 85 was not able to really care for the house or herself. This was yet another reason Mom wanted to be “out home”. The house and the 100 acres of land were jointly owned by Sister, my Mom and her sister, Kathryn. They had inherited it from Peter Stapleton Foster who was a brother to Mary Louise and father to my Mom and Aunt Kathryn.

The genealogy of a house can be very much tied to the genealogy of the family that owns it provided it isn’t sold out of the family as so many of these older plantation homes seem to be now. Most of these stately houses are now owned by people from somewhere else other than Franklin County and often are owned by people who have no roots at all in the county. Oak Grove has never left our family. It has passed down generation to generation. My children will be the 6th generation to own it. It may not be the biggest or most impressive of Franklin County plantation houses but the fact that it has never left the family and is essentially intact with original plaster and furniture does make it somewhat unique.

Peter Foster, the first of my family to come to Franklin County, was born in 1787 in Mathews County, Virginia. He purchased land in Franklin and Wake County.

Peter Foster 1787-1844. Oil Painting at Oak Grove

His eldest son, Augustus John Foster, took control of the Wake County plantation which was known as Wakefields and located in what is now Zebulon. Peter stayed on his plantation known as Locust Grove, a house that while no longer in the Foster family, is still standing and fully restored. He married Elizabeth Hardin Keeble and once settled in Franklin County, they raised 10 children. As Peter gained influence in Franklin County (he was postmaster, ran a store and started a school), he was able to acquire about 1300 of acres between his arrival in 1813 to the time that he died in 1844. At his death his property was split up among his children. Naturally, these 10 children argued over the property, eventually ending up in the Franklin County courts to solve it all. One tract of land was not in dispute and that was the tract given to Peter’s son, Dr. Peter Stapleton Foster. Born in 1823 and educated at William & Mary College and then University of Pennsylvania where he received his medical degree, Dr. Foster established a flourishing medical practice. He was often known to take a chicken for payment instead of cash if someone was struggling. He was not interested in a big flamboyant house like some. Oak Grove was not going to be confused with Montmorenci, the famous Warren County house of the Williams’ family. Oak Grove was, like Dr. Foster, a well-built Jacob Holt house without the fancy flourishes beyond some marbleized base boards and the usual Holt-style door and window surrounds along with a nice transom and side lights. Charles Mather Cooke wrote in Dr. Foster’s obituary that Dr. Foster was conservative and Oak Grove reflects that.

Dr. Foster built his practice and his farm with hard work and by 1860 was worth $55,000. It may not seem like much today, but that comes to over $1.5 million dollars in today’s money. He married Matilda Kearney Williams of Warren County, a family also known for some impressive homes such as Montmorenci.

Matilda Kearney Williams

Dr. Foster and his wife had 14 children but only seven lived to adulthood. Imagine losing half of your children? There are no family documents or diaries that tell us how they managed to work through the tragic loss of half of their children. On top of the loss of the children there was the fall out of the Civil War to deal with. Dr. Foster, by 1870, was worth only $900. From $55, 000 to $900 only 10 years later. Somehow, Peter and Matilda managed to hang on to Oak Grove. Dr. Foster was elected to the NC House of Commons in 1865 which, no doubt, helped him remain an influential presence in the community. Dr. Foster’s oldest son, Dr. Ernest Stapleton Foster, had established a successful medical practice in Louisburg so that left the second oldest son, Peter William Foster, to take over the farm at Oak Grove. He never became a politician nor would he become a doctor. He was a farmer and worked hard to keep the farm operating in the late 19th century and into the early 20th.

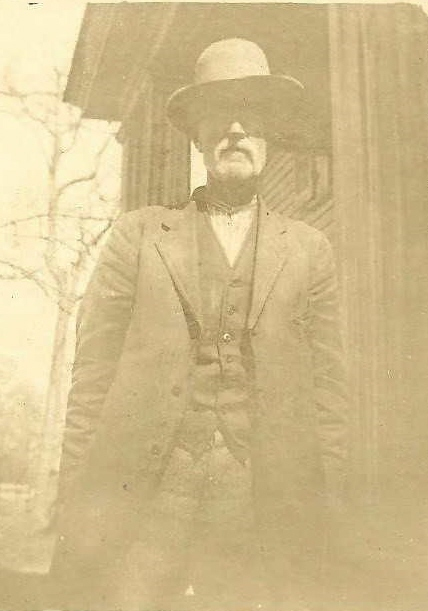

Peter William Foster at Oak Grove

He married Lutie Linwood Cooke and they had three children: Ernest Blacknall Foster, Mary Louise Foster and Peter Stapleton Foster.

Meanwhile, the house was becoming the place for family members to come for their final days. Dr. Peter Stapleton Foster’s bed, which is still in use today, saw 13 family members die in it. According to family lore, many family members returned to Oak Grove to pass. Whether it was due to Dr. Foster’s care or because it was home I can’t say. My wife, Aileen, will tell you the place is haunted. My wife, daughter and son have all claimed to see “the lady in black” which is believed to the Lutie Linwood Cooke. She was often photographed in all black.

Lutie Linwood Cooke

We’ve had a numerous ghost hunts at the house over the years. I remain a skeptic but even I have witnessed the occasional incident that I cannot explain.

After Peter William Foster died in 1920, the house was owned by Peter Stapleton Foster. He ran for county commissioner and spent several terms helping the people of Franklin County. It was during his ownership that we finally had indoor plumbing and electricity “out home”. An addition was built early in the Great Depression that would be used for a kitchen, bathroom and back porch which would eventually become a laundry room. The addition happened, in part, because Peter’s brother had become ill. Ernest suffered from cancer and was in pain the last seven years of his life. Having a bathroom in the house made life a little easier in his final year. He passed away in 1929 at the age of 33. It was said Uncle Ernest was a sleep walker and could often be seen coming down the steps carrying a candle or lantern. His brother would tell him to go back to bed and he would.

Ernest Blacknall Foster

Peter Stapleton Foster

Peter would die in 1950, one of the 13 to die in Dr. Foster’s bed. His wife, Ethel Collins Foster would pass away in 1959. Peter would be the last male Foster as he and Ethel had two daughters, Kathryn and Lutie. Kathryn, Lutie and Peter’s sister, Mary Louise would own Oak Grove jointly.

Kathryn and Lutie Foster at Oak Grove

My Aunt Kathryn is mostly responsible for my interest in old houses, history and genealogy. She was the family historian and made sure I took up the work after her passing in 2007. Lutie was my mother. Mary Louise, or Sister, as we called her, lived with her cousin, Matilda Brown throughout the 1960’s, and ‘70’s. Sister didn’t drive, never married and was retired from her job in Amityville, NY as a nurse. It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I found out many of the kids in the community were positively frightened of the house. I spoke with one of those kids after the passing of her father whom had been a family friend. She said she loved to go see Sister and Matilda but would not let them close the front door because she wanted to have an escape route. She was petrified of the house. Mark Pace, director of the NC Room at Thornton Library in Oxford also shared a similar story. His grandmother lived just a few miles up the road from Oak Grove and whenever they would pass the house he was told that it was haunted. Maybe it is, but the way I see it, it’s all of my family. So I’m not too worried about it.

Sister was known to like a drink and a smoke. She always had a pack of Kents with her and would enjoy a bourbon and Mountain Dew in the evenings. She was well into her 80’s by this point and would never dump the ashes from her cigarette. Once we moved “out home” my mom would follow Sister around the house with an ash tray as she feared Sister would set the house on fire. Sister died in 1976 shortly after the renovations were completed at the house. She died of complications from a broken hip and she never did burn the house down. We found money stuffed under mattresses, in drawers and in every other out of the way place. Sister didn’t trust banks very much. I still have her diary. After her passing, Oak Grove became the property of my mother and my aunt. They made the decision to sell 50 of the last remaining 100 acres of the Peter Foster holdings as my mom was living on social security and trying to raise me. My parents were older than most when I came along. Mom was 43 and Dad was 57. She needed the money for upkeep of the house, among other things. I was 25 when she died in 1988. Kathryn and I made the decision that I should get the house and several acres while Kathryn kept the other 45 acres which was still farmland that she rented out. Her son, Pete Joyner, inherited the property and since his passing a few years ago, the farm belongs to his wife, Maggui.

As the owner of Oak Grove, it’s my job to keep the place up. There’s always something that needs fixing, always a new project that needs to get started. At the moment those projects include removing the 1976 ceilings that my mother put up. We discovered beautiful tongue and groove ceilings under those pop corn ceilings from the 70’s. We are also removing carpet and laminate flooring and returning to the original hardwood floors. While they aren’t it perfect shape my wife, Aileen, and I are confident that with a little work this spring we can bring those floors back. My wife often says I love the house more than her. It’s true that I do love Oak Grove. There’s something timeless about these homes. They are so much more than just a house. I look at pictures from 60 or 70 years ago and see my Great Grandfather standing where I park my car every night. I never knew Peter William Foster but I know he’s a part of “out home” as his father is. I look at the portraits of these men and women that have hung on the walls of the house since 1850 realizing that in this day of “blip culture” where everything is over in an instant before we move on to the next big thing that there is a sense of permanence about Oak Grove and many of these older dwellings. They were here as part of the landscape long before I was born and I hope will be here for many more decades to come. I’ve lived at Oak Grove for 42 years and hope that I can spend quite a few more years “out home”.

Oak Grove today.

While it’s easy to for me to piece together the genealogy of my house since it’s remained in the family since its construction, it may not be so easy for others. We have so many people moving to our area and don’t know the families who were associated with the historic homes that have made their way on to the market. So how do you find out the genealogy of a house? The most straight forward way is to do a title search. This involves going to the deeds office and tracing the property back from owner to owner. However, it’s not as easy as it seems. Properties were more than likely parts of larger tracts of land. They would be split of and passed on to children of the original owner or may just be sold outright. Peter Foster’s holdings were split up for all of his children and when this happens it can become confusing. Wills are also useful, provided there is one. Libraries can also be essential if they house a room or section dedicated to local history with someone who knows the area in charge like Mark Pace in Oxford. These sources may help in finding out more information about the house and owners, perhaps leading to the discovery of family who had been associated with the house in years past. They may have access to family records, bibles and other information that can shed some light on an historic property. Many counties have published books on historic homes and county heritage. These publications are indispensable in learning about the people, the stories and the historic architecture that give a county its character.

Another great resource for leaning about a house is located here: http://gis.ncdcr.gov/hpoweb/ . As part of the State of North Carolina’s Dept. of Cultural Resources, this web site will show the location of all historic properties that have been documented in each county of the state. Many of these will have links to the forms used to place properties on the National Historic Register. These will give detailed information on ownership and architectural details.

There are many other resources available and the best course of action is ask questions. Dig deep! Finding out the history and genealogy of a house and its previous owners can be rewarding. It can lead to a deeper appreciation of the building and its history. Then you can have somewhere to call “out home.”

Peter Stapleton Foster. What would become US401 in background.